Menu

Blog: Resistance Materials

I grew up in a house that was full of political debate, but it wasn’t until I was a teen that I realized that my parents didn’t vote. “Why aren’t you voting?” I asked. “Why bother? We would cancel each other out!” they would joke. I asked the same question every election and they always had the same answer. As an adult, I understand that they had both internal barriers (“Politicians don’t care about us,”) and significant external barriers to voting. My parents lived in Fairmead, where, historically, many of the town’s residents were African-American farmers who had come west during the Dust Bowl and settled in the Central Valley decades ago. Californians might know Fairmead as the home of the last giant orange stand on Highway 99, where you could buy oranges and watch big rigs roar past, carrying produce to the rest of the nation, or they might remember Fairmead as the town of 1,400 people that made national headlines when its residents ran out of water. Because my parents worried about mail theft, if they had decided to vote, they would have taken public transportation to Chowchilla, five miles away, where most of the area’s libraries, community centers, parks and other shared resources are sited. At the latest, they’d start their trip at 1:15 pm, walk a mile to the bus stop in front of the Fairmead Baptist Church, take a five-mile bus ride to Chowchilla, vote and wait 2-3 hours for the next bus home. Despite the barriers, it is essential that we all vote. In the words of the late Representative John Lewis, "Your vote is precious - almost sacred, it is the most powerful non-violent tool we have to create a more perfect union." Every single vote is necessary to our democracy, and yet, too often, the people with the most insight into our nation’s most complicated problems – people with disabilities, people who live in low-income communities, immigrants, people of color and seniors – have multiple barriers to voting and face increasing disenfranchisement. This week, as I dropped my ballot in my neighborhood, legal, dropbox, I thought about my parents’ two votes, which wouldn’t have canceled each other out, they would have added two voices to an important conversation about all the things that affect their and our health, including bus rides, the lack of drinking water, access to services, and many others. I thought about that long paper ballot, and how it held the power of our voices, to improve shared health, address our most entrenched problems, strengthen our democracy, and how the act of voting was, in all our hands, an act of social transformation. I thought of the inimitable Representative John Lewis who risked his life to expand voting rights and who, in his final words to the nation, said, “Ordinary people with extraordinary vision can redeem the soul of America by getting in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble. Voting and participating in the democratic process are key. The vote is the most powerful nonviolent change agent you have in a democratic society. You must use it because it is not guaranteed. You can lose it.”

0 Comments

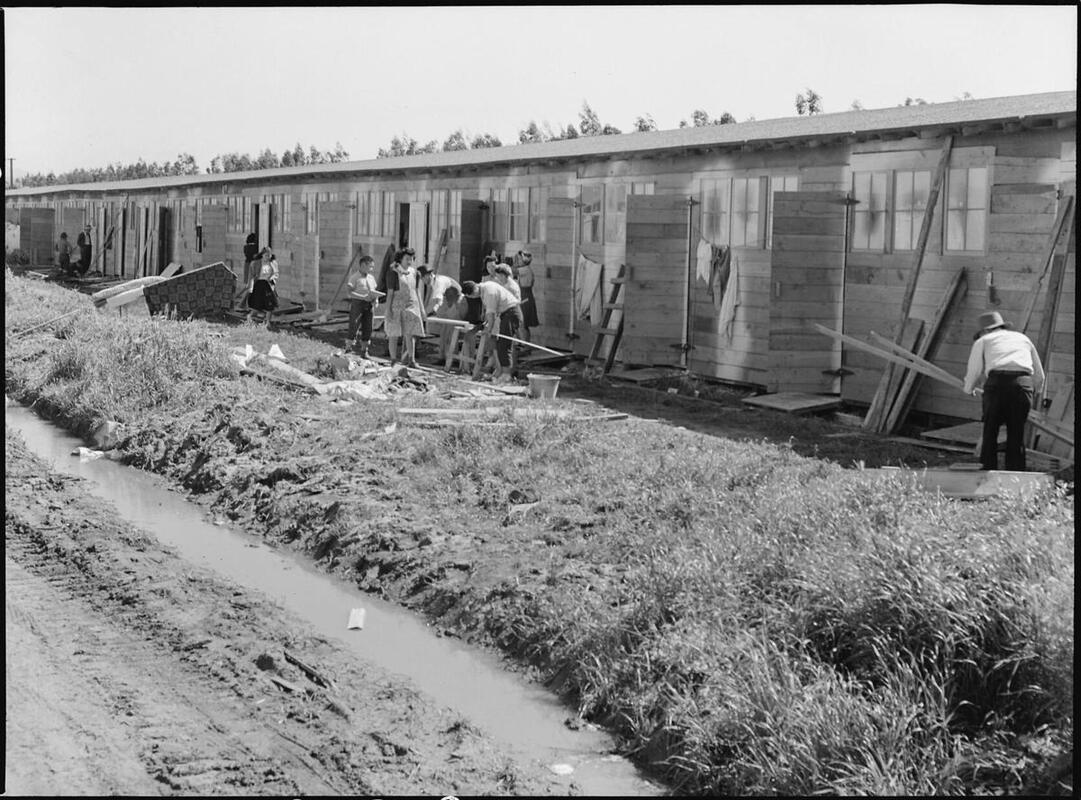

Earlier this year, I was late to work, flying down the stairs of the San Bruno BART station to the underground passenger area. The atmospheric rivers in the sky had filled the streets with water, slowing traffic, but I would have been late anyway. As usual, I had taken on too much work, both professional and volunteer. The San Bruno station is on the site of the old Tanforan Racetrack, which once confined Japanese Americans, mostly families, in horse stalls before they were sent to internment camps. This history, my family’s history, is documented in photo stories on the ground level of the station. I usually have a millisecond or less to reflect on that before I rush for the train. As I descended the stairs, I could see an older man in front of me. He was hunched over, wearing plain khaki pants, a faded button-down shirt, a light jacket and a hat with a local hardware store logo. His form, his bent shoulders, and the way he clung to the handrail, reminded me of all the people I knew growing up — people who had done hard agricultural labor over a lifetime. He stopped at the landing and clapped three times. I was just about to pass him, when I heard the clap echo in the vast chamber and also, in my head and heart. Whenever my grandfather faced a challenge, he would clap three times and call the Shinto spirits, as if to say, See me, I’m here and I’m trying. I stopped immediately and waited until the man was ready. I walked behind him, step by slow step, to the bottom. He didn’t clap again, we had made it. Shinto is the native Japanese religion. It focuses on appreciation and interconnectedness. Millions of Mari Kondo declutterers are performing a Shinto-like ritual as they thank their things for their service before throwing them away. I boarded the train and wondered how I had almost forgotten one of my most visceral childhood memories — my grandfather, who was famous for his physical strength, clapping three times. How did I forget? When I deboarded in San Francisco’s Financial District, I saw a throng of urgent office workers, pushing their way up the stairs because the escalators were out of service. I wondered how a busy crowd like that could see an old man struggling, let alone, make room for him, or anyone else who couldn’t keep up. Directly and indirectly, these are the exact questions that were explored at last month’s Fourth Annual Othering and Belonging Conference, which the Foundation was proud to support as part of our strategic direction to make California the healthiest state by addressing the root causes of poor health and inequity in our communities. A sense of belonging and acceptance is important to both physical and mental health, but it can be compromised by social inequities and divisions. john a. powell, Director of UC Berkeley’s Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, which organized the conference, offered a powerful premise for belonging as health, "We need each other. We share the earth and our dreams. This is the expanding story of ‘we’." The conference closed with an uplifting speech by Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II — minister, MacArthur Fellow, and political activist — whose Poor People’s Campaign has united disenfranchised low-income people across the country. If you want your hair to stand on end and feel the full passion of both moral outrage and social possibility, I encourage you to check out the video. When he finished, a coworker turned to me and said, “If you didn’t know, this is what it’s like to go to a Black church.” I smiled, “I need to go more often.” So, how many spirits live in a BART station? There was at least one who helped me hear the echo of a clap, and there was another three months later at a different station. Once again, the skies were full of rain and I was running to catch a train, bundled under jackets and scarves. As I slid into a cold seat, I realized that the chill I felt was not caused by the rain, my sneezes were not from allergies, and my sore muscles were not caused by a weekend hike. I had a cold. I immediately thought of the man in the San Bruno BART station. Back at work, I told my awesome team members I needed help and together, we rebalanced my workload. To me, the expanding story of “we” is about a convention center on Chochenyo land that can also serve as an ad hoc African American church. It is about a BART station where photo stories from the past evoke a sense of urgency about the present. It is about that deep sense of well-being that comes from a sense of belonging, and manifests as good health. It's about enduring connections to family, neighborhood, community, and culture. And most of all, it's about spirits in dark places who urge us to take good care of ourselves and each other. Photo republished from San Mateo Daily Journal. Photographer unlisted:

https://www.smdailyjournal.com/news/local/japanese-american-san-bruno-internment-camp-80-years-later/article_d0e63ecc-9140-11ec-9296-3b0f48a4bd51.html |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed